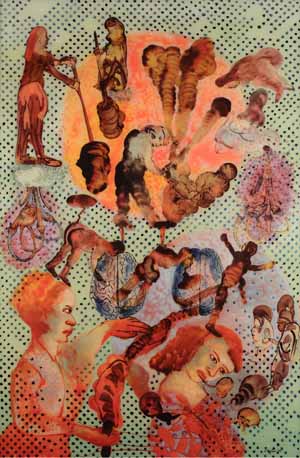

Appeasing Radha, triptych, 2006

NEW YORK TIMES OCTOBER 24, 2008-ROBERTA SMITH The Indian artist Nalini Malani practices a kind of manuscript illumination without the manuscript or any narrative logic at all. Both her paintings on acrylic and her magic-lantern installations layer scores of drifting, loosely drawn figures, animals, monsters and human organs (especially brains, spinal columns and intestines).

Her sources appear to include European engravings and medieval bestiaries, Indian painting, anatomical diagrams, American comic strips.

The result is a multicultural mélange of styles, myths and encounters that symbolize the all-too-human messiness of life — both psychic and physical, and especially where women are concerned — without seeming dreary. In the paintings this messiness is enriched by overripe, light-filled colors that almost glow from within because they are executed on sheets of clear acrylic. The magic-lantern installations are more monochromatic, but here the figures actually drift. They're painted on big cylinders of clear Mylar; when suspended, revolving and properly lighted, they cast layers of moving shadows on the wall.

Ms. Malani seems indebted to American artists like Nancy Spero, Ida Applebroog, Leon Golub and Kiki Smith, who have made similar use of illustrational styles. Whether or not this is true, her work surpasses theirs, thanks to its glowing, transparent colors; ease of execution; and visual richness. These qualities make it, despite its sometimes harsh subject matter, an essentially celebratory art, and one that for the most part has only gotten better.

FLASH ART JANUARY 2009, CHRISTOPHER HART CHAMBERS.

Nalini Malani’s show is on the epic scale and scope of a museum show: in fact two of the works were originally produced for Venice Biennales and a third commissioned by the Irish Museum of Modern Art. Her loose yet sure painting style combines the best elements of narrative abstraction and image pastiche, drawing on myths and tales from an international mélange of historic sources….. Malani’s lovingly rendered figures and motifs deftly balance naïve folk art influences and sophisticated paint handling. Her casts of disaffected protagonists float and meander through gorgeous tableaux. She commands a global resource of mythology with which she illustrated feminist and socio-political outrage.

THE BROOKLYN RAIL JUNE 2009,

POST MODERN CASSANDRA BY THOMAS McEVILLEY

Having met the Indian artist Nalini Malani in 1985, I have been following her work for nearly 25 years with increasing admiration. When I first knew her, Malani was primarily engaged with acrylic paintings on canvas or watercolors on paper that presented an essentially realistic, socially-based picture of life in contemporary India, focusing especially on gender and family issues. Grieved Child (1985), for example, represents a group of family and friends with great psychological and social subtlety1. Both engaging and socially engagé, the paintings became widely appreciated, first in India and, more recently, abroad. After the 1980s, Malani’s work became less oriented toward everyday life and more involved with the long and capacious Indian tradition. It was as if she were looking back over that history and seeing things hiding behind other things. She became increasingly concerned with the repressed, especially women’s issues. At the same time, she began to introduce the multicultural dimension that her own life reflects. Born in Karachi in 1946 when it was still in India, but shortly before it became part of a newly created Pakistan, she and her family soon relocated to Calcutta, in post-Partition India. Later, Malani traveled widely, spending a few years early on in Paris. Working within an increasingly international framework, she was especially drawn to earlier representations of female archetypes, from Hindu figures like Radha and Sita, to such Western icons as Medea and Alice.

Issues of gender and feminism remain central themes in a substantial exhibition, “Listening to the Shades,” at Arario Gallery in New York (founded in Korea, the gallery specializes in Asian art). No longer conventional paintings, most of Malani’s recent works are executed in acrylic and enamel on the reverse of a transparent surface like mylar. The method belongs to a tradition of reverse painting that goes back to Santiniketan in the early- to mid-20th century, and has something to do with the Hindu idea of maya, of an image taking form and apparent solidity in an ontological void.

When one of Malani’s series is seen complete—say the works in Splitting the Other (2006-07), which is composed of 14 vertical paintings each about 6½ by 3 feet—it can look like a dealt deck of cards. There is a sculptural aspect to the way such series can be arranged and rearranged and also, in certain configurations, a cinematic quality. Hung in a line, the panels of Splitting the Other seem to proceed with something like motion-picture vivacity. All these issues are engaged in the series called, like the exhibition, “Listening to the Shades” (2008). A principal work in the show, it is made up of 42 paintings of different sizes, most about 6 by 3 feet, with a few horizontal triptychs about three times that wide. With imagery that ranges from the visceral to the cosmic, it is epic in its reach.

Most cinematic are Malani’s signature projections of light through or from revolving acrylic cylinders bearing painted imagery. As the cylinders turn, the images (and the lights) move on the walls, crossing through and around one another in what Malani refers to as a shadow play. At Arario, the example was Remembering Mad Meg (2007), which was also included in Malani’s 2007 retrospective at the Irish Museum of Modern Art. The way the images merge, separate and move on seems to represent the currents of history as they shift across one another and are gone, and embodies the idea of maya even more intensely, as a drifting, ungraspable stream of images at once enticing and threatening.

Malani’s insistence on rooting herself in Indian culture while also addressing the rest of the world is perhaps the characteristic postmodern position. An important part of postmodernism is the global cry of women to each other, and in one sense that is what engages Malani’s current paintings. (In previous work not shown at Arario, in addition to that included in her 2002-03 exhibition at the New Museum, she also addressed such topical issues as the ethnic and ideological violence that occurred in Bombay in the early 90s. See Art in America, November 2003.)

Among the references to antiquity that can be found in Malani’s current painting (as throughout Indian culture) is her recollection of a standard neolithic icon in Medea I (2006). A mother goddess with an emphasized vagina is presented as the central axis of the pictorial field, surrounded by figures emanating from her. The series “Stories Retold: Mappings” (2007-08) shows another aspect of this female force. Its ten panels are connected by a kind of umbilical or intestinal interlacing that signifies energy or life force traveling through a cosmic female circuit. Splitting the Other (2008) also involves a unifying umbilical/intestinal element. In Medea III (2006), female icons from the Venus of Willendorf to modern pop idols occupy a world unified by Benday dots. Appeasing Radha (2006) is a triptych in which a goddess form that looks like it has been modeled of mud or dark gray clay is depicted in each of the flanking panels, amid a welter of flying figures. In the central panel, a physical or spiritual communion is illustrated.

There is a paranoid component to the feeling-tone of Malani’s paintings that is reflected in the title “Splitting the Other,” which suggests an aggressive subject-object relationship. Much of her work is dark and ominous; she has been described by one critic as among midnight’s children. Yet there is also a good deal of sunshine and a certain amount of transcendent illumination in her paintings, and sometimes, as when (in recent paintings not shown at Arario) they feature the Alice-in-Wonderland theme, they are almost lighthearted. The texture and tonality of Malani’s pictorial surfaces are lyrical in a deeply layered, dreamlike way. In this shifty, moody terrain, archetypes not only appear out of history but compose it, as signposts and directional signals.

In a sense, these floating archetypal images are the “shades” in the exhibition title. It seems that for Malani, the title also describes something that happens while she is engaged in making—or finding—the work. Listening to the shades may be her term for paying attention to her inner voices as they drift upward from the darkness of her unconscious, and of the collective unconscious. Drawing them up and promoting their clarity is the work of the artist.

There is a lot going on in these paintings. In panel six of Splitting the Other, for example, two angelic figures stand on a giant brain in the middle of the sky, radiating solar beams. This part looks like an image of tantric union. Below it, the lower world is represented, as it often was in alchemical symbolism, as a dog. A spinal column ascends to unify the above and below and provide a channel of ascent or descent. Up on high is some kind of struggle among monstrous beings. There is a great deal going on, and hints of a narrative that cannot really be filled out. The general texture of this symbolic universe resembles the pictorial surface of ancient Egyptian artwork; Malani recalls that her mother took her to Egypt at age 12 and that it made a deep impression. Other works can be analyzed in comparable detail. But some revert to the absolute simplicity and centrality of iconicity, as in the Medea paintings in “Listening to the Shades,” where the ancient witch stands gleaming like a savage fire at the very center of a mostly empty rectangle.

In a recent text by Malani, she more or less assumes the role of Cassandra, a figure from the archaic and early classical period (primarily known from Aeschylus’s Oresteia) who has second sight and freely declares what she sees but, apparently because she is a woman, is not believed. For Malani, Cassandra signifies the unhappy fact that “profound insights that individuals have that can be good for the future of humankind are not paid heed to and we continue in the direction of death and destruction.”2 Yet Malani, a kind of Cassandra of postmodern art, has found a way to get her message across.

1. See Thomas McEvilley, “The Common Air: Contemporary Art in India,” Artforum, Summer 1986.

2. Nalini Malani, “Cassandra,” in Robert Storr, Nalini Malani, Listening to the Shades, New York, Charta and Arario, 2008, n.p.

“Nalini Malani: Listening to the Shades” was on view at Arario Gallery, New York [Sept. 18-Oct. 25, 2008].